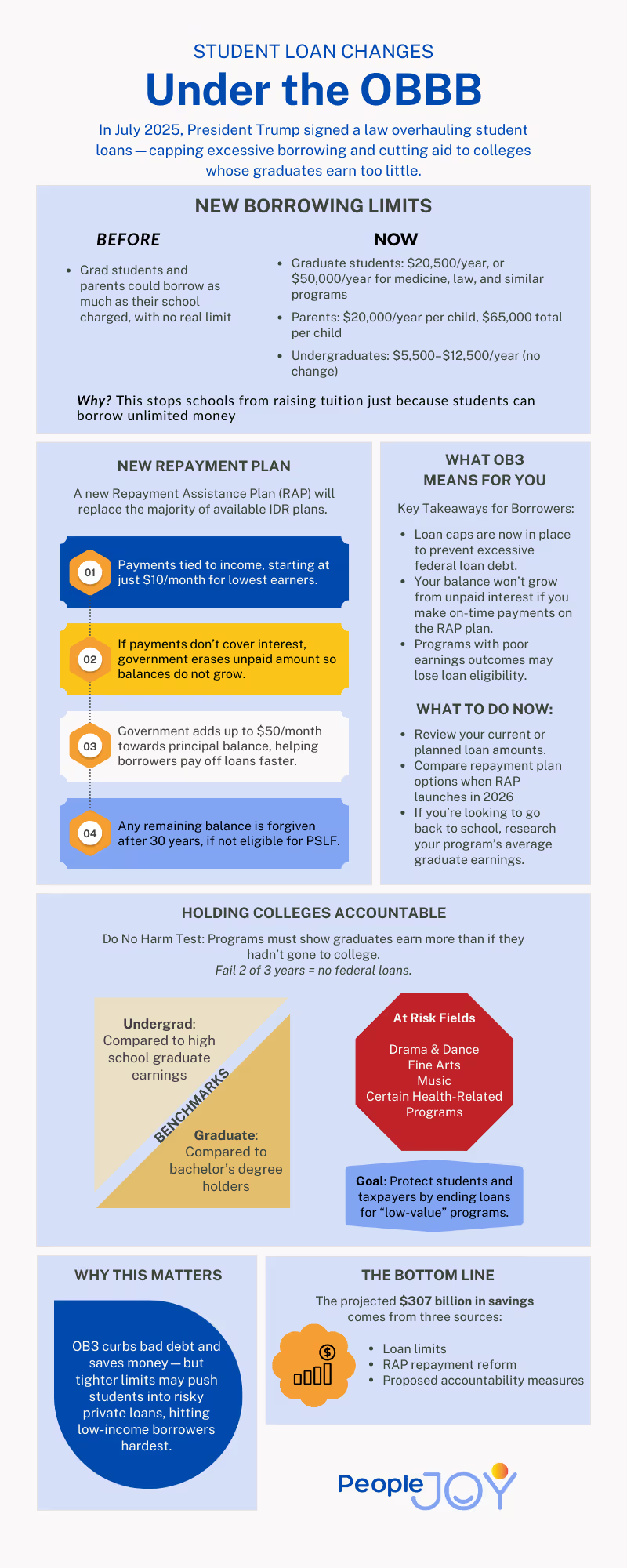

When the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB)—from here on out referred to as OB3—was signed into law in July 2025, it marked the most sweeping student loan reform in years. While its official goal is to make federal spending more efficient, the bill also introduces changes designed to curb runaway borrowing, protect borrowers from spiraling debt, and hold colleges accountable for student outcomes.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), these reforms will save $307 billion over the next decade. But the real story isn’t just about the savings—it’s about how the bill reshapes the student loan system for the future.

1. Smarter Borrowing Limits

For decades, graduate students and parents could borrow almost unlimited amounts to cover tuition and living expenses. This often led to skyrocketing debt—and in some cases, it encouraged schools to raise prices.

OB3 introduces clear caps:

- Graduate students: $20,500/year ($50,000 for certain professional programs like law or medicine)

- Parents of undergrads: $20,000/year per child, with a $65,000 lifetime cap

- Undergraduates: Existing limits remain ($5,500–$12,500/year

By setting boundaries, OB3 aims to push high-cost programs to reconsider tuition and prevent families from taking on debt they can’t realistically repay.

2. A Repayment Plan That Stops Debt Growth

One of the most frustrating realities of student loans is negative amortization—when payments don’t even cover the interest, causing the balance to grow.

The new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) under OB3 changes that:

- Payments are tied to income, starting at just $10/month for the lowest earners.

- If payments don’t cover the interest, the government erases the unpaid amount so balances never grow.

- The government also adds up to $50/month toward the principal, helping borrowers pay off loans faster.

- Any remaining balance is forgiven after 30 years, though most borrowers will finish much sooner.

Compared to older plans like PAYE or the now-repealed SAVE plan, RAP reduces forgiveness costs for taxpayers while giving borrowers a clear path to zero debt.

3. Holding Colleges Accountable

OB3 introduces a “Do No Harm” test that evaluates whether a degree program increases graduates’ earnings. If a program fails for two out of three years, it loses access to federal loans.

- Undergraduate programs are compared to the earnings of high school graduates.

- Graduate programs are compared to similar bachelor’s degree holders.

- Low-performing fields—like drama, dance, fine arts, and certain health programs—are most at risk.

This change means taxpayer dollars won’t fund programs with little to no economic return, and students will have better information before enrolling.

The Bottom Line for Taxpayers and Borrowers

The projected $307 billion in savings from OB3 comes from three sources:

- Loan limits that reduce excessive borrowing and discourage tuition inflation.

- RAP repayment reform that prevents ballooning balances and limits forgiveness payouts.

- Accountability measures that end funding for low-value degree programs.

For taxpayers, this means a leaner, more sustainable loan system.

For borrowers, it means smarter debt, faster payoff timelines, and protection from runaway interest.

Why This Matters Now

Student loan debt in the U.S. has topped $1.7 trillion, and political debates over forgiveness have been fierce. OB³’s approach doesn’t erase debt overnight, but it reshapes the system to be fairer, more efficient, and more focused on real outcomes.

It’s a shift from “how can we forgive debt?” to “how can we prevent bad debt in the first place?”—and that’s a conversation worth having.

However, there’s another side to consider: tighter federal loan limits could push some students—especially those in expensive graduate or professional programs—toward private loans. Unlike federal loans, private loans often have higher interest rates, fewer repayment protections, and no forgiveness options. This can make it harder for borrowers to get out of debt and can hit lower-income students the hardest, potentially discouraging them from pursuing advanced degrees altogether.

The long-term challenge will be making sure that while bad debt is reduced, access to higher education—particularly for students from lower-income backgrounds—remains open and affordable.

%20Financial%20Wellness%20Programs%20That%20Actually%20Improve%20Teacher.avif)